The first «entente cordiale» between France and England took shape with a highly symbolic gesture: Queen Victoria's visit to King Louis-Philippe between 2 and 7 September 1843, at the Château d'Eu in Normandy. It was the first time since Henry VIII that a British sovereign had visited France. This friendly event was all the more impressive given that, three years earlier, the two countries had been on the brink of confrontation over the question of the Orient, and strong resentment had ensued in public opinion on both sides of the Channel. The appointment of a new government on 29 October 1840, with François Guizot as Foreign Minister, was seen as a first sign of appeasement. In August 1841 George Hamilton Gordon, Earl of’

The first «entente cordiale» between France and England took shape with a highly symbolic gesture: Queen Victoria's visit to King Louis-Philippe between 2 and 7 September 1843, at the Château d'Eu in Normandy. It was the first time since Henry VIII that a British sovereign had visited France. This friendly event was all the more impressive given that, three years earlier, the two countries had been on the brink of confrontation over the question of the Orient, and strong resentment had ensued in public opinion on both sides of the Channel. The appointment of a new government on 29 October 1840, with François Guizot as Foreign Minister, was seen as a first sign of appeasement. In August 1841 George Hamilton Gordon, Earl of’ The quality of relations between London and Paris soon improved. In fact, the friendship between the two sovereigns, which manifested itself in the French king's visit to the Queen of England at Windsor in October 1844 and Victoria's brief visit to Eu in September 1845, took on its full dimension through the increasingly close ties that the bourgeois minister forged with the great Scottish lord.

The quality of relations between London and Paris soon improved. In fact, the friendship between the two sovereigns, which manifested itself in the French king's visit to the Queen of England at Windsor in October 1844 and Victoria's brief visit to Eu in September 1845, took on its full dimension through the increasingly close ties that the bourgeois minister forged with the great Scottish lord. In October 1843, he coined the phrase «a new way of life".A cordial good understanding»In December, in the Throne Speech inspired by Guizot, Louis-Philippe echoed this by speaking of «sincere friendship» and a spirit of «cordial understanding». Victoria used the same expressions before Parliament in February 1844. The entente cordiale was not an alliance enshrined in a treaty, but a state of mind thus defined by the French minister on 22 January 1844: «On certain questions, the two countries have understood that they can agree and act in common, without any formal commitment, without any alienation of any part of their freedom». It was soon based on an original approach: the two colleagues established a private correspondence between themselves, unbeknownst to their colleagues, their parliaments and their diplomatic agents, the aim of which was formulated as follows by Guizot in a letter to Aberdeen dated 9 March 1844: «Basically, we want the same things. So we can tell each other everything. We are honest people. So we can always believe each other. And that's exactly what they did, until they left Aberdeen in June 1846. This method enabled them to resolve difficulties and overcome crises that could have got out of hand: the right to visit each other's ships to prevent the slave trade; the protectorate established by France over Tahiti, with what has been called the »Pritchard affair«, which unleashed passions on both sides; French intervention in Morocco; rivalries between ambassadors in Athens and Madrid... Each time, personal contacts between the two ministers, through sometimes very frank explanations between men, managed to put out the fire and preserve the peace, which was the foundation of their policy. To do this, they had to brave the attacks of the parliamentary opposition, and sometimes the incomprehension of their own political friends. While Aberdeen was accused of »kissing the ground before the French ally«, his colleague was branded »Lord Guizot«. One particularly sensitive issue, the marriages of the young Spanish Queen Isabella and her sister, at a time when France and England had long been rivals in Madrid, seemed to have been resolved by a fair compromise when Peel was overthrown in June 1846. Palmerston succeeded Aberdeen and opted for a showdown with Paris. Guizot, who had a long-standing dispute with him, took up the challenge and, not without brutality, had the Spanish marriages concluded to the advantage of French policy. In October, the entente cordiale was buried. The fact remains that France and England will never again wage war against each other.

In October 1843, he coined the phrase «a new way of life".A cordial good understanding»In December, in the Throne Speech inspired by Guizot, Louis-Philippe echoed this by speaking of «sincere friendship» and a spirit of «cordial understanding». Victoria used the same expressions before Parliament in February 1844. The entente cordiale was not an alliance enshrined in a treaty, but a state of mind thus defined by the French minister on 22 January 1844: «On certain questions, the two countries have understood that they can agree and act in common, without any formal commitment, without any alienation of any part of their freedom». It was soon based on an original approach: the two colleagues established a private correspondence between themselves, unbeknownst to their colleagues, their parliaments and their diplomatic agents, the aim of which was formulated as follows by Guizot in a letter to Aberdeen dated 9 March 1844: «Basically, we want the same things. So we can tell each other everything. We are honest people. So we can always believe each other. And that's exactly what they did, until they left Aberdeen in June 1846. This method enabled them to resolve difficulties and overcome crises that could have got out of hand: the right to visit each other's ships to prevent the slave trade; the protectorate established by France over Tahiti, with what has been called the »Pritchard affair«, which unleashed passions on both sides; French intervention in Morocco; rivalries between ambassadors in Athens and Madrid... Each time, personal contacts between the two ministers, through sometimes very frank explanations between men, managed to put out the fire and preserve the peace, which was the foundation of their policy. To do this, they had to brave the attacks of the parliamentary opposition, and sometimes the incomprehension of their own political friends. While Aberdeen was accused of »kissing the ground before the French ally«, his colleague was branded »Lord Guizot«. One particularly sensitive issue, the marriages of the young Spanish Queen Isabella and her sister, at a time when France and England had long been rivals in Madrid, seemed to have been resolved by a fair compromise when Peel was overthrown in June 1846. Palmerston succeeded Aberdeen and opted for a showdown with Paris. Guizot, who had a long-standing dispute with him, took up the challenge and, not without brutality, had the Spanish marriages concluded to the advantage of French policy. In October, the entente cordiale was buried. The fact remains that France and England will never again wage war against each other.

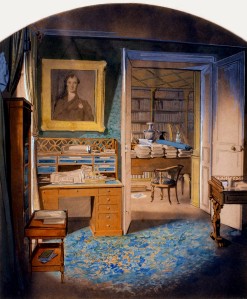

Finally, the cordial understanding between Guizot and Aberdeen gave rise to a true and deep friendship which, in the case of the more expansive Guizot, took on an affectionate, even passionate tone: «All yours from the bottom of my soul», he concluded in a letter of July 1846. In 1847, they exchanged portraits, which they hung in their respective salons. This beautiful relationship, never altered for a moment, lasted until Aberdeen's death in 1860: «He loved me and I loved him,» wrote Guizot at the time. «It was a true, intimate friendship, and I would gladly say a tender one if it had to be said between men.»