[To access the article in pdf format, click here here. To read it online, follow the page navigation].

The file relating to the relationship between the Hachette bookshop and François Guizot is exceptionally well supplied, and would merit publication in its own right, not so much for the six publishing contracts it contains as for the abundant correspondence that accompanies them - although this only emanates from the publisher - as well as for the precious account statements.

When, in the spring of 1852, the fifty-year-old Louis Hachette came to present Guizot with a project that he declared to be original, he was no stranger to him. Twenty years earlier, he had become one of the main publishers of the textbooks that the Minister of Public Education Guizot had commissioned for his major project to develop primary education in France. But this was the first time he had signed a contract in his own name. Hachette, whose head office at the time was located at 14 rue Pierre-Sarrazin before moving to 77 boulevard Saint-Germain six years later, had obtained a licence from the railway companies, in return for a fee of 30%, to sell small volumes in stations, forming a «Railway Library». Keen to diversify its offer, Hachette proposed to Guizot, who accepted, to «provide a few volumes written, if not by you, at least under your direction and with the indication of your assistance on the title.[1]»These works would cover the history of England and the United States. The author could choose between two methods of remuneration: either, in accordance with the traditional formula, a flat fee of 150 francs per sheet of printed matter, representing 32 pages in the in-18° format used for the Library; or three centimes per sheet for each volume, payable on publication, with 100 francs per sheet being paid on submission of the manuscript, «which would be deducted from the proceeds of copyright up to the appropriate amount», in other words a sort of «à-valoir", based as always, it is true, not on actual sales but on print runs. It took a month of negotiation to reach an agreement, because Guizot, in asking for a higher royalty, was defending the interests of the authors he had to recruit and employ, as well as remunerating, as well as his own. Hachette, for his part, argued that the price at which he wanted to sell works intended for the general public was low, that he had to pay royalties to the railway companies, and that Guizot was not personally the author, - "and one can, without touching the merit of the collaborators you have chosen, be less sure of the success of their works than of yours".[2]» -. And he assumed the pose of offended dignity in the face of Guizot's apparent distrust of him: «You speak to us of some arrangements to be made to ascertain the number of editions and copies printed. There is not one of the many authors with whom we are in contact who does not rely on our loyalty for this.[3]»Finally, on 30 August 1852, the following provisions were agreed: «M. Guizot undertakes to have twelve volumes written at his own expense and under his direction and review» with the following titles, eight relating to the history of England and four to that of the United States, mainly biographies. The volumes may not exceed six to eight printed sheets, i.e. 192 to 256 pages. The title of each work may or may not bear the name« of its author, but must include the words »...«.reviewed by M. Guizot». So it was the latter's name that the publisher was buying. In the end, it cost him five centimes per printing sheet for each copy printed, i.e. 30 to 40 centimes, with a «à valoir» - the words are there now - of 100 francs per sheet when the manuscript was handed in. At least 3,000 copies of each work will be printed, representing an average royalty of around 1,000 to 1,200 francs. In addition, a double pass hand will be printed «in addition to each ream», which protects the author's interests since he is guaranteed the set print run, to «cover print run defects, copies distributed free of charge and the thirteenths that are customary in the book trade». Finally, Guizot makes it clear that the publishers «will inform him by letter of the editions that may be made and the numbers at which they should be printed».»

When, in the spring of 1852, the fifty-year-old Louis Hachette came to present Guizot with a project that he declared to be original, he was no stranger to him. Twenty years earlier, he had become one of the main publishers of the textbooks that the Minister of Public Education Guizot had commissioned for his major project to develop primary education in France. But this was the first time he had signed a contract in his own name. Hachette, whose head office at the time was located at 14 rue Pierre-Sarrazin before moving to 77 boulevard Saint-Germain six years later, had obtained a licence from the railway companies, in return for a fee of 30%, to sell small volumes in stations, forming a «Railway Library». Keen to diversify its offer, Hachette proposed to Guizot, who accepted, to «provide a few volumes written, if not by you, at least under your direction and with the indication of your assistance on the title.[1]»These works would cover the history of England and the United States. The author could choose between two methods of remuneration: either, in accordance with the traditional formula, a flat fee of 150 francs per sheet of printed matter, representing 32 pages in the in-18° format used for the Library; or three centimes per sheet for each volume, payable on publication, with 100 francs per sheet being paid on submission of the manuscript, «which would be deducted from the proceeds of copyright up to the appropriate amount», in other words a sort of «à-valoir", based as always, it is true, not on actual sales but on print runs. It took a month of negotiation to reach an agreement, because Guizot, in asking for a higher royalty, was defending the interests of the authors he had to recruit and employ, as well as remunerating, as well as his own. Hachette, for his part, argued that the price at which he wanted to sell works intended for the general public was low, that he had to pay royalties to the railway companies, and that Guizot was not personally the author, - "and one can, without touching the merit of the collaborators you have chosen, be less sure of the success of their works than of yours".[2]» -. And he assumed the pose of offended dignity in the face of Guizot's apparent distrust of him: «You speak to us of some arrangements to be made to ascertain the number of editions and copies printed. There is not one of the many authors with whom we are in contact who does not rely on our loyalty for this.[3]»Finally, on 30 August 1852, the following provisions were agreed: «M. Guizot undertakes to have twelve volumes written at his own expense and under his direction and review» with the following titles, eight relating to the history of England and four to that of the United States, mainly biographies. The volumes may not exceed six to eight printed sheets, i.e. 192 to 256 pages. The title of each work may or may not bear the name« of its author, but must include the words »...«.reviewed by M. Guizot». So it was the latter's name that the publisher was buying. In the end, it cost him five centimes per printing sheet for each copy printed, i.e. 30 to 40 centimes, with a «à valoir» - the words are there now - of 100 francs per sheet when the manuscript was handed in. At least 3,000 copies of each work will be printed, representing an average royalty of around 1,000 to 1,200 francs. In addition, a double pass hand will be printed «in addition to each ream», which protects the author's interests since he is guaranteed the set print run, to «cover print run defects, copies distributed free of charge and the thirteenths that are customary in the book trade». Finally, Guizot makes it clear that the publishers «will inform him by letter of the editions that may be made and the numbers at which they should be printed».»

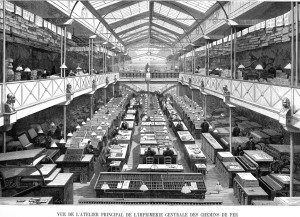

The terms of the negotiation and the contract are easier to understand when you know that Guizot was not on his first try. In fact, at the very beginning of 1851, a draft treaty had been drawn up between him and Napoléon Chaix, a printer since 1845 at 20 rue Bergère, and since 1849 the happy publisher of the’Railway Indicator and guides for travellers, and so are already well established in stations . He had conceived the project of a Universal Library which, according to his prospectus, «through the most advantageous financial conditions would make available to all, and could spread among the most modest classes of society, the enlightenment of Religion, the lessons of the Moralists, the masterpieces of literature and the teachings of Science». Guizot accepted «the philosophical and literary direction of this vast undertaking». The Bibliothèque universelle, which would consist of at least 500 in-8° volumes of around 500 pages, divided into series of 100 volumes sold for no more than 1.80 francs, would be published under the name of M. Guizot. He would choose the titles, write or have written either translations or complete works, or prefaces, notes and analyses. He would receive five centimes per volume from the sales price and after collection, and not from the print run, which was a novelty. It would set up a seven-member editorial board to oversee the successful completion of selected publications. Each editor would receive five centimes for each volume sold to which he contributed, and an attendance fee of 10 francs for meetings held every fortnight. The agreement was concluded for ten years, with Guizot undertaking to supply one hundred volumes each year, so that the Library would be set up in five years. Chaix expected at least 6,450 subscribers per series for the whole of France, i.e. an annual sale of 645,000 volumes, which would generate 32,250 francs for the director of the Bibliothèque. The project was taken quite far, since Guizot drew up lists of works intended for the Library, and lined up the names of possible contributors, always the same ones, those of his friends V. de Broglie, Vitet, Barante, Lenormant, Dumon, and also Abbés Gerbet and Gratry.

. He had conceived the project of a Universal Library which, according to his prospectus, «through the most advantageous financial conditions would make available to all, and could spread among the most modest classes of society, the enlightenment of Religion, the lessons of the Moralists, the masterpieces of literature and the teachings of Science». Guizot accepted «the philosophical and literary direction of this vast undertaking». The Bibliothèque universelle, which would consist of at least 500 in-8° volumes of around 500 pages, divided into series of 100 volumes sold for no more than 1.80 francs, would be published under the name of M. Guizot. He would choose the titles, write or have written either translations or complete works, or prefaces, notes and analyses. He would receive five centimes per volume from the sales price and after collection, and not from the print run, which was a novelty. It would set up a seven-member editorial board to oversee the successful completion of selected publications. Each editor would receive five centimes for each volume sold to which he contributed, and an attendance fee of 10 francs for meetings held every fortnight. The agreement was concluded for ten years, with Guizot undertaking to supply one hundred volumes each year, so that the Library would be set up in five years. Chaix expected at least 6,450 subscribers per series for the whole of France, i.e. an annual sale of 645,000 volumes, which would generate 32,250 francs for the director of the Bibliothèque. The project was taken quite far, since Guizot drew up lists of works intended for the Library, and lined up the names of possible contributors, always the same ones, those of his friends V. de Broglie, Vitet, Barante, Lenormant, Dumon, and also Abbés Gerbet and Gratry.  We don't know why or how Hachette took Chaix's place, but this affair undoubtedly played a part in the hatred that Hachette pursued Chaix until his death in 1865. Napoléon Chaix must have felt dispossessed of an idea he had conceived first. As for Guizot, it is probable that going from one hundred to twelve annual volumes, proportionately better paid, offered a return to the principle of reality. How would he have managed to manage the enormous project envisaged by Chaix with the rigour he was known for? Chaix did launch, under his own name, a Universal family library, but without being able to rise to the level of the Railway library.

We don't know why or how Hachette took Chaix's place, but this affair undoubtedly played a part in the hatred that Hachette pursued Chaix until his death in 1865. Napoléon Chaix must have felt dispossessed of an idea he had conceived first. As for Guizot, it is probable that going from one hundred to twelve annual volumes, proportionately better paid, offered a return to the principle of reality. How would he have managed to manage the enormous project envisaged by Chaix with the rigour he was known for? Chaix did launch, under his own name, a Universal family library, but without being able to rise to the level of the Railway library.

The contract signed with Hachette would be all the more advantageous for Guizot as he would be able to recruit authors at low cost. In fact, he asked his son Guillaume to write about Alfred the Great, and his daughter Henriette to write about William the Conqueror and Edward III. Paul Lorain, his son François's tutor at the end of the Restoration and later his close collaborator at the Ministry of Public Instruction, and very close to Louis Hachette, whose pupil he had been at the École Normale, was also enlisted and trusted Guizot with the conditions that would be imposed on him: «As far as I am concerned, and I dare say as far as my son-in-law is concerned, without having spoken to him about it, as you cannot fail both by your spirit of justice and by your precious friendship for both of us, to obtain honest remuneration for our work, I can only ask you to do what you have always done, to stipulate for me better than I can.[4]»The son-in-law was Camille Rousset, Guillaume Guizot's history teacher in the late 1840s, who had become a family friend. He dealt with the Magna Carta, his father-in-law with the origin and founding of the United States. It is likely that the editor, who conscientiously carried out his editing work, paid half of his remuneration to his authors, whose names did appear on the title page, with the exception of that of Henriette de Witt. Perhaps fearing that historians would impose their academic conceptions of history, the publisher insisted on the necessary accessibility of the books he was responsible for: «Our collection is intended for a very special public, for travellers who will take our books not to study, but to shorten the time of their journey.[5]»How much did the «History and Travel» series in the Railway Library earn Guizot? Edward III and the burghers of Calais, for example, was published five times during Guizot's lifetime, and three more times up to 1887.

In March 1855, the Revue des deux mondes published a historical study by Guizot entitled «L'amour dans le mariage». A contract was immediately signed with Hachette for a small-format edition, and even then «with the necessary blanks to make the volume four leaves long». In fact, the printer Charles Lahure, whose workshop was located at 9 rue de Fleurus, produced a 92-page in-18° volume. . The author received 15 centimes per copy printed, the first edition being set at 5,000 copies, or 750 francs payable on sale. For the first time, the clause relating to passing on mentions «copies used for advertising», in other words the press service. Although the assignment was made without any time limit, the rights for the English language were naturally reserved. Sales began at a brisk pace. Hachette, an active and enterprising publisher, proposed to the author, following the first reprint, that «in order to prolong the success of this little book and meet the demands of the public, which is always asking for cheap publications, the price per copy be reduced to 50 centimes», which would reduce royalties by two-thirds, or five centimes. But the next print run would be 10,000 copies instead of 3,000, and «this increase in sales would certainly compensate you for the reduction in your royalties.[6]»Does lowering the price of books encourage sales in proportion? The debate is still going on. In any case, Guizot was not convinced, and made a counter-proposal to reduce the price from 1 franc 50 to 75 centimes, with himself receiving 10 centimes per copy. Hachette rejected this «half-measure», because his intention was to «compete» with the 50-centime publications that were developing.[7]. Consequently, 3,000 copies of the third edition were printed under the same conditions as the previous ones. Guizot was undoubtedly not wrong, as ten editions followed one another until 1873, with a total of 32,000 copies generating 4,800 francs in royalties.

. The author received 15 centimes per copy printed, the first edition being set at 5,000 copies, or 750 francs payable on sale. For the first time, the clause relating to passing on mentions «copies used for advertising», in other words the press service. Although the assignment was made without any time limit, the rights for the English language were naturally reserved. Sales began at a brisk pace. Hachette, an active and enterprising publisher, proposed to the author, following the first reprint, that «in order to prolong the success of this little book and meet the demands of the public, which is always asking for cheap publications, the price per copy be reduced to 50 centimes», which would reduce royalties by two-thirds, or five centimes. But the next print run would be 10,000 copies instead of 3,000, and «this increase in sales would certainly compensate you for the reduction in your royalties.[6]»Does lowering the price of books encourage sales in proportion? The debate is still going on. In any case, Guizot was not convinced, and made a counter-proposal to reduce the price from 1 franc 50 to 75 centimes, with himself receiving 10 centimes per copy. Hachette rejected this «half-measure», because his intention was to «compete» with the 50-centime publications that were developing.[7]. Consequently, 3,000 copies of the third edition were printed under the same conditions as the previous ones. Guizot was undoubtedly not wrong, as ten editions followed one another until 1873, with a total of 32,000 copies generating 4,800 francs in royalties.

It was a more traditional contract which, like the previous one, on 31 July 1862 gave the form of a book to a work being published in the Revue des deux mondes, Un projet de mariage royal«. This work of at least 300 pages, in fact 360, »printed in the typeface of love in marriage»It will be part of the «Bibliothèque variée», priced at 3 francs 50 per in-18° volume by Jésus. This was the last contract to bear the signatures of Guizot and Louis Hachette, whose health was already failing and who died exactly two years later, aged 64. Émile Templier, born in 1821, his son-in-law since 1849 and from then on one of his two managing partners, had been in contact with Guizot for some time and, from 1855 onwards, most of the letters signed by his father-in-law and addressed to Guizot are in his handwriting. Guizot liked this «intelligent, well-mannered and eager" man.[9]». He was of the same generation as Michel Lévy, the most active competitor of Hachette and now of Templier, and Guizot, who esteemed them equally, held the balance between them equal, so much so that he sometimes received them both on the same day, one in the morning and the other in the evening. Each of them was careful and intelligent not to pose as rivals to their common author. So Michel Lévy made no attempt to divert to his own advantage the trust that Guizot placed in Templier when he contracted with him for his last and very large publishing operation. I saw Michel Lévy yesterday,« announced Guizot on 31 October 1869, "and I told him that I had reached an agreement with Hachette. He was expecting it (...) We will remain on good terms.[10]»And he confirmed this in a letter.[11] For his part, Lévy returned the courtesy: «You couldn't put the care of your interests in better hands.[12] »

This was the last contract to bear the signatures of Guizot and Louis Hachette, whose health was already failing and who died exactly two years later, aged 64. Émile Templier, born in 1821, his son-in-law since 1849 and from then on one of his two managing partners, had been in contact with Guizot for some time and, from 1855 onwards, most of the letters signed by his father-in-law and addressed to Guizot are in his handwriting. Guizot liked this «intelligent, well-mannered and eager" man.[9]». He was of the same generation as Michel Lévy, the most active competitor of Hachette and now of Templier, and Guizot, who esteemed them equally, held the balance between them equal, so much so that he sometimes received them both on the same day, one in the morning and the other in the evening. Each of them was careful and intelligent not to pose as rivals to their common author. So Michel Lévy made no attempt to divert to his own advantage the trust that Guizot placed in Templier when he contracted with him for his last and very large publishing operation. I saw Michel Lévy yesterday,« announced Guizot on 31 October 1869, "and I told him that I had reached an agreement with Hachette. He was expecting it (...) We will remain on good terms.[10]»And he confirmed this in a letter.[11] For his part, Lévy returned the courtesy: «You couldn't put the care of your interests in better hands.[12] »

In fact, on 30 July, Guizot had written to Émile Templier to find out whether the Hachette bookshop, of which Templier was «one of the two oldest partners to whom the social signing of treaties with authors is reserved», would publish a History of England told by M. Guizot to his grandchildren and written by his daughter Mme de Witt, in three volumes of around 500 pages, and a History of France told by M. Guizot to his grandchildren. Templier was immediately interested. But, so as not to overlook any possible outcome, and also out of good manners, Guizot also approached Michel Lévy: «I propose to write the’History of France (...) I have kept my notes. It will be 4 to 6 volumes in-8°.

In fact, on 30 July, Guizot had written to Émile Templier to find out whether the Hachette bookshop, of which Templier was «one of the two oldest partners to whom the social signing of treaties with authors is reserved», would publish a History of England told by M. Guizot to his grandchildren and written by his daughter Mme de Witt, in three volumes of around 500 pages, and a History of France told by M. Guizot to his grandchildren. Templier was immediately interested. But, so as not to overlook any possible outcome, and also out of good manners, Guizot also approached Michel Lévy: «I propose to write the’History of France (...) I have kept my notes. It will be 4 to 6 volumes in-8°. Guizot ceded to Hachette, «for as long as his literary property and that of his heirs or representatives lasts, either according to current legislation or according to future legislation» - a new wording taking into account the evolution of the law which appears in the contracts concluded thereafter - the editorial exclusivity of a "literary property". History of France, from the earliest times to 24 February 1848, told to my grandchildren, The first, from the origins to 1789, was in three volumes, the second, from 1789 to 1848, in one volume. The idea was to publish in instalments, with illustrations, at a price of five centimes per copy, with a minimum initial print run of 5,000. If both parties agreed to a volume edition, the author would receive one franc for the in-8° format and 50 centimes for the in-18° format. The rights to the English language are reserved for the author, and the others are shared with the publisher, who, in all cases, may sell the engraving plates for his own profit. If the publisher does not reprint an edition within three months of it going out of print, the author's rights revert to the publisher, but the plates remain the property of the publisher.

Guizot ceded to Hachette, «for as long as his literary property and that of his heirs or representatives lasts, either according to current legislation or according to future legislation» - a new wording taking into account the evolution of the law which appears in the contracts concluded thereafter - the editorial exclusivity of a "literary property". History of France, from the earliest times to 24 February 1848, told to my grandchildren, The first, from the origins to 1789, was in three volumes, the second, from 1789 to 1848, in one volume. The idea was to publish in instalments, with illustrations, at a price of five centimes per copy, with a minimum initial print run of 5,000. If both parties agreed to a volume edition, the author would receive one franc for the in-8° format and 50 centimes for the in-18° format. The rights to the English language are reserved for the author, and the others are shared with the publisher, who, in all cases, may sell the engraving plates for his own profit. If the publisher does not reprint an edition within three months of it going out of print, the author's rights revert to the publisher, but the plates remain the property of the publisher.

It was in these conditions that this exceptional undertaking was launched. No doubt Guizot had been thinking about this work for a long time, and had included it in the contract signed with Gosselin in 1838. But today he is 82 years old, and although his vigour of spirit is intact, his old age has set in. The lessons he has been giving to his grandchildren at Val-Richer for several years now were undoubtedly prepared by him and recorded by his daughter Henriette, but putting them across to a wider audience is an altogether different exercise. Émile Templier, however, did not hesitate to take the risk of an unfinished story.

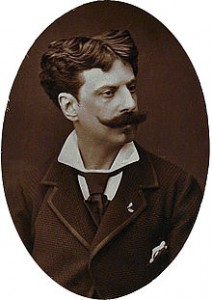

It was in these conditions that this exceptional undertaking was launched. No doubt Guizot had been thinking about this work for a long time, and had included it in the contract signed with Gosselin in 1838. But today he is 82 years old, and although his vigour of spirit is intact, his old age has set in. The lessons he has been giving to his grandchildren at Val-Richer for several years now were undoubtedly prepared by him and recorded by his daughter Henriette, but putting them across to a wider audience is an altogether different exercise. Émile Templier, however, did not hesitate to take the risk of an unfinished story. , And for four years, the great man's hand did not tremble, until, in the last few months, his daughter wrote under his dictation. Twelve days after signing the contract, Templier received the first 114 pages of the manuscript. Inaugurating a process that was to be repeated dozens of times, this text was sent to the draughtsman Alphonse de Neuville, who produced the large and small woodcuts intended to illustrate each chapter. Guizot supplied him with documents and sometimes adjusted his text to the illustrations, to which he paid extreme attention, starting with the captions. Alphonse de Neuville reassured him: «My Simon de Montfort will be killed according to all the rules of the art of sieges in the Middle Ages, by an exact mangonel, on a horse caparisoned with his arms as given by his seal.[14]»

, And for four years, the great man's hand did not tremble, until, in the last few months, his daughter wrote under his dictation. Twelve days after signing the contract, Templier received the first 114 pages of the manuscript. Inaugurating a process that was to be repeated dozens of times, this text was sent to the draughtsman Alphonse de Neuville, who produced the large and small woodcuts intended to illustrate each chapter. Guizot supplied him with documents and sometimes adjusted his text to the illustrations, to which he paid extreme attention, starting with the captions. Alphonse de Neuville reassured him: «My Simon de Montfort will be killed according to all the rules of the art of sieges in the Middle Ages, by an exact mangonel, on a horse caparisoned with his arms as given by his seal.[14]»

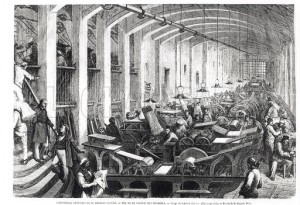

The first of the weekly issues, each of 16 pages in-4° with illustrations occupying the equivalent of two pages, was published on 15 April 1870, with a print run of 15,000 copies following a canvassing and advertising campaign, which was repeated on a larger scale for the launch of the next three volumes. The first three issues were sent to 62 newspapers, from l'Avenir national à the Breton Union, by way of the Young people's diary[15]. A prospectus drafted by Guizot was sent to secondary schools and boarding schools, and a page of advertising was purchased in the newspaper Fashion illustrated, with a print run of 83,000 copies. Many incidents got in the way of a production whose regularity was an essential factor of success: a car accident and the indisposition of the illustrator, strikes by the workers at the printer Simon Raçon who, at other times, was overwhelmed, delays in drying the printed sheets despite the newly installed wind tunnels... and above all the war with Prussia, then the Commune, so that publication was interrupted with the 16th anniversary of the French Revolution.e delivery at the end of August 1870, only to resume in mid-June 1871. The author, for his part, continued writing with no apparent weariness, delivering his text with clockwork regularity, much to Templier's relief. The first bound volume, in 4° format, containing the first 37 issues, i.e. some 800 manuscript pages, went on sale in November 1871, in time for the end-of-year shopping that the publisher had high hopes for, as the work was an ideal gift for young and old alike. A few weeks later, Guizot's biographical study of his old and dear friend Victor de Broglie, who had died in January 1870, was published in book form in September-October 1871 in the Revue des deux mondes. Templier immediately made known his desire to publish it, not without «pointing out that the sale of this volume will necessarily be very limited.[16]»So the contract signed on 6 October set copyright at 50 centimes per copy, while the contract signed on 7 October set copyright at 50 centimes per copy, while the contract signed on 7 October set copyright at 50 centimes per copy. the Duc de Broglie, published in the «Bibliothèque variée», was 300 pages long. It was printed in 1,500 copies, but, following a technique that was in full development, photographs of the composition were taken for rapid reprinting in the event of success. Guizot wanted a photograph of his friend to be inserted at the head of the book, but «this would cost us between 75 centimes and 1 franc per volume, and the price of the notice would be increased accordingly, which would jeopardise its sale.[17]»and Guizot had to see reason.

The first of the weekly issues, each of 16 pages in-4° with illustrations occupying the equivalent of two pages, was published on 15 April 1870, with a print run of 15,000 copies following a canvassing and advertising campaign, which was repeated on a larger scale for the launch of the next three volumes. The first three issues were sent to 62 newspapers, from l'Avenir national à the Breton Union, by way of the Young people's diary[15]. A prospectus drafted by Guizot was sent to secondary schools and boarding schools, and a page of advertising was purchased in the newspaper Fashion illustrated, with a print run of 83,000 copies. Many incidents got in the way of a production whose regularity was an essential factor of success: a car accident and the indisposition of the illustrator, strikes by the workers at the printer Simon Raçon who, at other times, was overwhelmed, delays in drying the printed sheets despite the newly installed wind tunnels... and above all the war with Prussia, then the Commune, so that publication was interrupted with the 16th anniversary of the French Revolution.e delivery at the end of August 1870, only to resume in mid-June 1871. The author, for his part, continued writing with no apparent weariness, delivering his text with clockwork regularity, much to Templier's relief. The first bound volume, in 4° format, containing the first 37 issues, i.e. some 800 manuscript pages, went on sale in November 1871, in time for the end-of-year shopping that the publisher had high hopes for, as the work was an ideal gift for young and old alike. A few weeks later, Guizot's biographical study of his old and dear friend Victor de Broglie, who had died in January 1870, was published in book form in September-October 1871 in the Revue des deux mondes. Templier immediately made known his desire to publish it, not without «pointing out that the sale of this volume will necessarily be very limited.[16]»So the contract signed on 6 October set copyright at 50 centimes per copy, while the contract signed on 7 October set copyright at 50 centimes per copy, while the contract signed on 7 October set copyright at 50 centimes per copy. the Duc de Broglie, published in the «Bibliothèque variée», was 300 pages long. It was printed in 1,500 copies, but, following a technique that was in full development, photographs of the composition were taken for rapid reprinting in the event of success. Guizot wanted a photograph of his friend to be inserted at the head of the book, but «this would cost us between 75 centimes and 1 franc per volume, and the price of the notice would be increased accordingly, which would jeopardise its sale.[17]»and Guizot had to see reason.

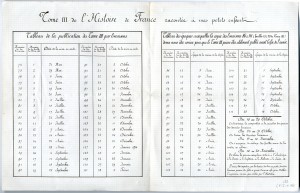

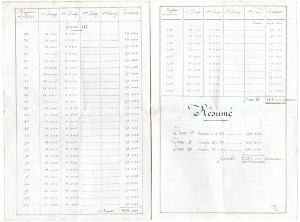

The first issue of Volume II went on sale in the third week of February 1872. Templier soon expressed a fear that would grow throughout the year, even if it was partly feigned to stimulate the author, that of running out of copy: «We only have six issues left, which means enough to appear for six weeks; and that is precisely the time we need to prepare the illustration for an issue. If you were unable to provide us with copy very soon, it is to be feared that our publication would be interrupted. Nothing could be more unfortunate. To fix the work schedule for the year, Templier had an extraordinary table drawn up showing the number of the delivery and the number of the printing sheet, the time when the copy would be delivered - every five days until 10 October - and the time when it would go on sale, so that the bound volume would be available on 20 November. Guizot organised himself accordingly: «I will certainly do François II in the last ten days of June - Charles IX in three or four weeks of July - Henri III from 29 July to 15 or 20 August. For Henry IV, I will have seven or eight weeks left until 15 October. That will be my finishing touch.[21]»It should be remembered that he was in his 85s at the time.e year. He fulfilled his programme within a few days, sending off his last consignment on 9 November, and volume III went on sale in mid-December. He set to work on the fourth volume without respite, which resumed publication at the end of July 1874, each with a print run of 15,000 copies. Despite the death of his daughter Pauline in February, which shook him to the core, he worked at Le Val-Richer without respite, sending copies of six of the thirteen chapters making up volume IV between June and July. But from then on he dictated to Henriette, because the handwriting in his trembling hand was becoming illegible. On 28 August, Templier wrote to her: «We are well on the way to completing Volume IV», and expressed the hope that his health would improve. A few days later, overcome by weakness, Guizot took to his bed and died on 12 September. The last chapter of volume IV, which it is not certain he had time to dictate, was devoted to the death of Louis XIV. It was Henriette who took charge of the fifth volume, «written according to the plan and notes of M. Guizot», the first issue of which was published in March 1875, and which she completed with two volumes covering the period from 1789 to 1848, published in 1878-1879.

To fix the work schedule for the year, Templier had an extraordinary table drawn up showing the number of the delivery and the number of the printing sheet, the time when the copy would be delivered - every five days until 10 October - and the time when it would go on sale, so that the bound volume would be available on 20 November. Guizot organised himself accordingly: «I will certainly do François II in the last ten days of June - Charles IX in three or four weeks of July - Henri III from 29 July to 15 or 20 August. For Henry IV, I will have seven or eight weeks left until 15 October. That will be my finishing touch.[21]»It should be remembered that he was in his 85s at the time.e year. He fulfilled his programme within a few days, sending off his last consignment on 9 November, and volume III went on sale in mid-December. He set to work on the fourth volume without respite, which resumed publication at the end of July 1874, each with a print run of 15,000 copies. Despite the death of his daughter Pauline in February, which shook him to the core, he worked at Le Val-Richer without respite, sending copies of six of the thirteen chapters making up volume IV between June and July. But from then on he dictated to Henriette, because the handwriting in his trembling hand was becoming illegible. On 28 August, Templier wrote to her: «We are well on the way to completing Volume IV», and expressed the hope that his health would improve. A few days later, overcome by weakness, Guizot took to his bed and died on 12 September. The last chapter of volume IV, which it is not certain he had time to dictate, was devoted to the death of Louis XIV. It was Henriette who took charge of the fifth volume, «written according to the plan and notes of M. Guizot», the first issue of which was published in March 1875, and which she completed with two volumes covering the period from 1789 to 1848, published in 1878-1879.

During the five years of this immense project, the publisher accompanied his author step by step, alternately accommodating or firm, pressing or reassuring, attentive to the technical aspects of production as well as to the commercial action, reporting to him on everything, always courteous and sometimes moved, in short placing him in the best working conditions. In this respect, the dozens of letters, sometimes very detailed, sent by Émile Templier and sometimes, in his absence, by Jean Georges Hachette, Louis's youngest son, who became a partner in the bookshop at the age of 26 shortly before his father's death, provide exceptional testimony.  The company's success was considerable, not only in France but throughout the world.[22]. A summary table of sales of the 109 issues making up the first three volumes, drawn up in July 1874, shows that by that date they had each sold between 19,000 and 25,000 copies, reaching the enormous total of 2,239,000, or 111,950 francs paid to the author, not counting the royalties from the bound volumes, which were republished several times. To this must be added the proceeds from translations, starting with the English language, for which the London publisher Sampson Low, based at 188 Fleet Street, had acquired the rights for £100 per volume.[23].

The company's success was considerable, not only in France but throughout the world.[22]. A summary table of sales of the 109 issues making up the first three volumes, drawn up in July 1874, shows that by that date they had each sold between 19,000 and 25,000 copies, reaching the enormous total of 2,239,000, or 111,950 francs paid to the author, not counting the royalties from the bound volumes, which were republished several times. To this must be added the proceeds from translations, starting with the English language, for which the London publisher Sampson Low, based at 188 Fleet Street, had acquired the rights for £100 per volume.[23].

- Letter signed Louis Hachette, 7 July 1852.↵

- Idem of 23 July 1852.↵

- Ibidem.↵

- Letter dated 12 July 1852.↵

- Letter signed Louis Hachette dated 1er August 1852.↵

- Letter signed Louis Hachette, 21 September 1855.↵

- Idem of 25 September 1855.↵

- The Jesus-sized printing sheet provides sixteen leaves, i.e. thirty-six pages measuring 18.5 cm x 11.5 cm, for the in-18° edition.↵

- Letter from Guizot to his daughter Henriette, 27 October 1869. See François Guizot, Letters to his daughter Henriette (1836-1874), op. cit., p. 959.↵

- François Guizot, Letters to his daughter Henriette (1836-1874), op. cit., p. 961.↵

- Letter dated 11 November 1869: «I regret that we were unable to reach agreement on my History of France as told to my grandchildren. When the opportunity arises, I will gladly take it to express my desire to maintain the good business relations we have had with you.»↵

- Letter of 1er November 1869. By way of compensation, Guizot offered Lévy the chance to bring together in one volume various writings that had appeared separately. The latter declined: «This competing publication would lead to unfortunate comparisons for me commercially speaking. You will therefore understand, dear Mr Guizot, that it will be very difficult for me to publish anything by you for as long as Messrs Hachette are publishing your History of France. »↵

- Letter dated 10 August 1869.↵

- Letter from A. de Neuville dated 18 June 1871.↵

- In a review published in June 1870 in The Correspondent, the critic Pierre-Paul Douhaire regretted that the illustrations contained too much nudity. A. de Neuville replied that «the Barbarians wore very little clothing, but we have reached the period where the naked were about to disappear». Templier's letter to Guizot dated 15 June 1870.↵

- Letter from Templier dated 22 September 1871.↵

- Idem, 6 October 1871↵

- Idem, 11 March 1872.↵

- Idem, 5 September 1872.↵

- Idem, 24 October 1872.↵

- Letter dated 18 June 1873. Cf. François Guizot, Letters to his daughter Henriette (1836-1874), op. cit., p. 1021.↵

- An edition was in the personal library of Viacheslav Molotov, Stalin's top man, who died in 1986. See Rachel Polonsky, Molotov's magic lantern. A journey through Russian history, Paris, Denoël, 2012.↵

- The History of France from the earliest times to the year 1789, by M. Guizot, translated by Robert Black. S. Low, Marston, Low & Searle. The five volumes appeared between 1872 and 1883. This edition was distributed in the United States by Estes & Lauriat, 143 Washington Street, Boston.↵