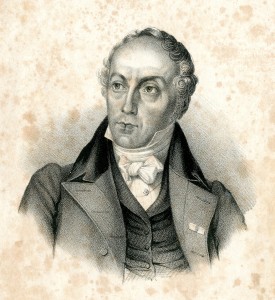

When François Guizot became the seventh Minister of Public Education under the July Monarchy on 11 October 1832, he had long been a recognised specialist in educational issues. Since 1812, he had been Professor of Modern History at the Faculty of Letters in Paris, and even his most resolute opponents agree that he was the greatest history teacher in France in the early nineteenth century. In addition, with his future wife Pauline de Meulan, he founded in 1811 and wrote for three years the Annals of Education, This was a monthly magazine for families and teachers wishing to keep abreast of ideas, methods and works designed to ensure the successful education of children and pupils. From the time it was founded in 1815, it had been a member of the Société pour l'instruction élémentaire (Society for Elementary Education), which supported in particular mutual teaching, which had come from England and was very much in vogue at the time.  In 1815, both as an academic and as Secretary General of the Ministry of the Interior, he was the main architect of the royal decree of 17 February on the reform of public education. The preamble to this text, which circumstances prevented from being implemented but which in 86 articles contains a whole plan for the decentralised reorganisation of the University into seventeen academies, states that «the true purpose of national education is to propagate sound doctrines, maintain good morals and train men who, by their enlightenment and virtue, can give back to society the useful lessons and wise examples they have received from their teachers».»

In 1815, both as an academic and as Secretary General of the Ministry of the Interior, he was the main architect of the royal decree of 17 February on the reform of public education. The preamble to this text, which circumstances prevented from being implemented but which in 86 articles contains a whole plan for the decentralised reorganisation of the University into seventeen academies, states that «the true purpose of national education is to propagate sound doctrines, maintain good morals and train men who, by their enlightenment and virtue, can give back to society the useful lessons and wise examples they have received from their teachers».»

Above all, Guizot was led, against the attacks of the untraceable Chamber advocating the control of the Catholic clergy over education, to come to the defence of the University and to clarify his own ideas in a brochure published in 1816, Essay on the history and current state of public education in France, The first page establishes a principle: «The State provides education and instruction for those who would not receive it without the State, and undertakes to provide it for those who wish to receive it from the State». Guizot then distinguishes between the three levels of education - primary, secondary and special - and specifies their content, starting with «the precepts of religion and morality». The author explains that while ignorance «makes the people turbulent and ferocious», as the French Revolution proved, national education makes it possible to establish «either between the government and the citizens, or between the various classes of society, a certain community of opinions and feelings which will become a powerful bond, a guarantee of rest and a principle of effective order». With religion and morality at the service of the «government of minds» and social order through education, the essence of Guizot's action in power has already been said.

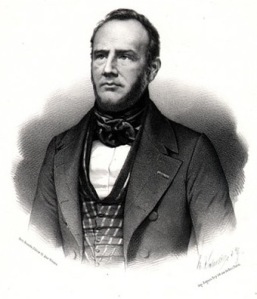

Thus, in October 1832, Guizot was well equipped to occupy 116 bis rue de Grenelle. The ministry's central administration was lean: the minister's office, headed by Alphonse Génie, and his secretariat; three divisions: personnel and administration, divided into five offices, the last of which was devoted to Protestant affairs - a new feature; general accounting and legal affairs, with three offices; and finally the division of science and literature, headed by Hippolyte Royer-Collard. , Pierre-Paul's nephew, and his two sections. With the two cashiers, there were scarcely more than twenty full-time civil servants. It is true that Guizot called on outside help, such as Charles de Rémusat, MP for Haute-Garonne and his disciple for fifteen years, or Paul Lorain, a graduate of the Ecole Normale Supérieure from the class of 1817. As Grand Master of the University, the Minister was also in his capacity as President of the Royal Council for Public Education, which had six members around him, including his famous former colleagues from the Sorbonne during the Restoration, Cousin for philosophy and Villemain for literature, and Ambroise Rendu, whom he made a very valuable assistant. The Council appointed the twelve Inspectors General, as well as the Director of the École normale supérieure, then Guigniaut. The Minister paid extreme attention to personal relations with all those involved in the common work, because, he later wrote, «of all the ministerial departments, public education is perhaps the one where it is most important for the minister to spare the opinion of the men around him, and to secure their support in his undertakings (...) In no branch of government do the choice of men, the relations of the leader with his associates, personal influence and mutual trust play such a large role».»

, Pierre-Paul's nephew, and his two sections. With the two cashiers, there were scarcely more than twenty full-time civil servants. It is true that Guizot called on outside help, such as Charles de Rémusat, MP for Haute-Garonne and his disciple for fifteen years, or Paul Lorain, a graduate of the Ecole Normale Supérieure from the class of 1817. As Grand Master of the University, the Minister was also in his capacity as President of the Royal Council for Public Education, which had six members around him, including his famous former colleagues from the Sorbonne during the Restoration, Cousin for philosophy and Villemain for literature, and Ambroise Rendu, whom he made a very valuable assistant. The Council appointed the twelve Inspectors General, as well as the Director of the École normale supérieure, then Guigniaut. The Minister paid extreme attention to personal relations with all those involved in the common work, because, he later wrote, «of all the ministerial departments, public education is perhaps the one where it is most important for the minister to spare the opinion of the men around him, and to secure their support in his undertakings (...) In no branch of government do the choice of men, the relations of the leader with his associates, personal influence and mutual trust play such a large role».»

Guizot's task was twofold. Firstly, to rebuild primary education in France, which had been abandoned by the public authorities since the end of the Ancien Régime. Secondly, to implement Article 69 of the revised Charter, promulgated on 14 August 1830, which was to provide for «public instruction and freedom of education». This issue was part of the wider question of relations between the State and the Churches, legally regulated by the Concordat and the organic articles of 1802, but also by specific texts that varied according to the political situation. The early days of the July monarchy were marked by a sometimes virulent anti-clericalism, which the Minister of Public Education had to take into account. The fact remains that, as he said in a speech in February 1832, «to truly found constitutional government, to fight successfully against the forces that attack it» - revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries - «we need the support of religion and of the clergy as a religious establishment». This conviction, which was as much political as it was intellectual and moral, formed the basis of all Guizot's actions.

His five-title, twenty-six-article bill on primary education, which was initiated in October 1832 and presented to the Chamber of Deputies on 2 January 1833, was well received. This text, as the minister declared, was «essentially practical», and «really had no other object than that which it openly proposes, the greater good of the education of the people». The principle of compulsory education was not retained, even though «a list of children who, not receiving primary education at home, should be required to attend public schools, with the permission or at the request of their parents» was to be drawn up. The principle of free education was not retained either, but poor families were exempted from paying school fees. ![]() On the positive side, the law sets out the minimum and compulsory content of elementary and higher primary education. It establishes the principle of freedom of primary education, with the formula «primary education is either public or private». In the case of public schools, this freedom is recognised for all individuals, subject to conditions laid down by law, namely a certificate of competence and a certificate of good character issued by the public authorities. Public schools are maintained by communes, départements or the State, with each commune having to maintain a primary school with a paid and housed teacher, and each département a teacher training college. A local supervisory committee was responsible for inspecting the public and public schools in the commune, and an arrondissement committee for all those within its jurisdiction. This committee appointed public schoolteachers on presentation of candidates by the commune committee. Finally, a final article opened up the possibility of establishing communal girls' schools, an initiative that Parliament rejected without any real opposition from Guizot.

On the positive side, the law sets out the minimum and compulsory content of elementary and higher primary education. It establishes the principle of freedom of primary education, with the formula «primary education is either public or private». In the case of public schools, this freedom is recognised for all individuals, subject to conditions laid down by law, namely a certificate of competence and a certificate of good character issued by the public authorities. Public schools are maintained by communes, départements or the State, with each commune having to maintain a primary school with a paid and housed teacher, and each département a teacher training college. A local supervisory committee was responsible for inspecting the public and public schools in the commune, and an arrondissement committee for all those within its jurisdiction. This committee appointed public schoolteachers on presentation of candidates by the commune committee. Finally, a final article opened up the possibility of establishing communal girls' schools, an initiative that Parliament rejected without any real opposition from Guizot.

All in all, this short text sought to establish, rather than competition, complementarity between the State and the Churches - essentially the Catholic Church - in the provision of primary education. There were no real substantive objections to its discussion, as developing primary education was an idea that was all the more readily accepted given that neither the elected representatives nor most of the electorate sent their children to primary schools. Only one important point was hotly debated, and rejected by the committee: the presence by right of a minister of religion - a parish priest or minister - on the local supervisory committee, which would otherwise be made up of the mayor and three municipal councillors. How, replied Guizot, having unanimously accepted in Article 1 that «moral and religious instruction» should be at the head of primary education, could we exclude from the supervision of schools «the moral and religious magistrate» who is the parish priest or pastor in each commune? And then, if the parish priest is benevolent, the committee will be fine; if he is not, which can happen, it is better to have him inside, annihilated by the four secularists, than outside, where he risks founding a rival school to the public school, which he will deplore with all his might, while, by his legal exclusion, the entire clergy, the vast majority of whom are healthy, will be offended. The majority of the deputies nevertheless supported the committee's opinion, and it was only at the second reading that the presence of the parish priest was re-established on the supervisory committee, whose powers were nevertheless reduced. The left-wing deputy Taillandier exclaimed: «You are creating a bone of contention in every commune if you allow the mayor and the parish priest to supervise the school at the same time». The law, which had passed its first reading in the House on 3 May by 249 votes to 7, was only passed by 219 votes to 57 on 18 June. It was promulgated ten days later.

This text, hardly innovative in itself, was the ambiguous fruit of a necessary compromise. This is undoubtedly the root cause of its success and posterity. The obligation to open communal and teacher-training colleges, the elevation of teachers to the status of public servants appointed by the Minister, the recruitment everywhere of teachers recognised as capable, the supervision exercised by the public authorities over all establishments, all established the State as responsible for and guarantor of primary education. For all that, and albeit within a framework, freedom of education was real, even if the State was now imposing competition on public schools that many of them would find difficult to withstand, and Guizot was explicitly counting on this. The clergy, while not excluded from the operation of public schools, was kept at a fair distance, and religion was placed in the forefront of education.

Application of the law

La  Above all, the application of the law gave rise to a considerable number of circulars, the most famous of which, drafted by Rémusat, is the following that of 4 July 1833 sent to all primary school teachers in France, with the text of the law, to explain to them the spirit and the means with which to accomplish their mission. The letter, also dated 4 July, addressed to the rectors and prefects, stated that public education also included the salles d'asile, «where small children aged between two and six or seven are received, who are still too young to attend primary school proper, and whose parents, poor and busy, do not know how to keep them at home (...) They are the foundation and, so to speak, the cradle of popular education». At the other end of the scale are the adult schools, «where the generation already hard at work, already engaged in active life, can receive the instruction that their childhood lacked».

Above all, the application of the law gave rise to a considerable number of circulars, the most famous of which, drafted by Rémusat, is the following that of 4 July 1833 sent to all primary school teachers in France, with the text of the law, to explain to them the spirit and the means with which to accomplish their mission. The letter, also dated 4 July, addressed to the rectors and prefects, stated that public education also included the salles d'asile, «where small children aged between two and six or seven are received, who are still too young to attend primary school proper, and whose parents, poor and busy, do not know how to keep them at home (...) They are the foundation and, so to speak, the cradle of popular education». At the other end of the scale are the adult schools, «where the generation already hard at work, already engaged in active life, can receive the instruction that their childhood lacked».

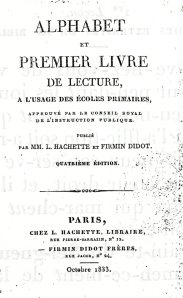

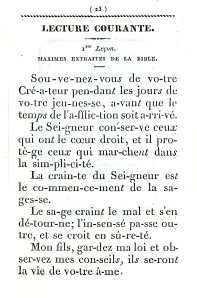

The Ministry did more than simply issue circulars to teachers and those responsible for primary education. As soon as he arrived at rue de Grenelle, Guizot created a General manual of primary education, This was designed to inform teachers and members of local supervisory committees about all issues, methods and publications relating to primary education. It was responsible for publishing and distributing textbooks, which were distributed free of charge to needy children. In 1833, the latter represented 23% of primary school pupils on average, but more than half in some départements.

Four hundred and fifty thousand copies were sent to schools in 1833, with the following headlines the Alphabet and first reading book, The anonymous author was Ambroise Rendu. The Guizot law soon produced impressive results.

The Report to the King of 14 April 1834 stated that there were 33,695 state primary schools for boys (compared with 31,420 the previous July), 1,650,000 pupils (compared with 1,200,000) and 62 teacher training colleges (compared with 47). By the end of 1847, this figure had risen to 43,514 schools with 2,176,000 pupils and 76 teacher training colleges. In addition, the level of teaching staff, many of whom were now graduates of better-quality teacher training colleges, appeared to have risen significantly.

Secondary education

Guizot was no less interested in secondary education, but none of the reform projects in this area came to fruition until the end of the July monarchy. The question of primary education was posed in different terms. While in one case it was a question of reorganising and extending a form of education for which nobody disputed that the main responsibility should lie with the State, in the other, the system existed legally and socially; what remained was to introduce the freedom promised by the Charter, in other words, to put an end to the monopoly granted to the University in 1808. Guizot, in his Memoirs, put it graphically: «I had to introduce freedom into an institution where it did not naturally exist, and at the same time defend that institution itself against formidable assailants. I had to guard the place and open its doors at the same time. The right solution, he added, would have been to »completely renounce the principle of State sovereignty, and frankly adopt the principle of free competition between the State and its rivals, whether secular or ecclesiastical, individuals or corporations«. Politically, he was not in a position to do so, nor did he have the will to do so. The difficulties that arose during the discussion of the law on primary education encouraged him to delay. »It was quite deliberate«, he told the deputies on 29 May 1835, »that I did not ask for this law (on secondary education) to be presented to you earlier; it is because the questions associated with it are not, for myself, sufficiently resolved«. In 1835, according to some estimates, there was one pupil for every 493 inhabitants. Most of the departmental capitals did not have a royal college, i.e. a lycée. These lycées enrolled 14,500 pupils, and, at the lower level, the communal colleges, the second type of public establishment, enrolled only 23,700. Public schools took in slightly more, 28,000 in institutions and boarding houses and 16,600 in the one hundred and twenty-one authorised minor seminaries, making a total of less than 83,000 pupils. These were undoubtedly the children of the middle and especially the upper classes, from which voters and elected representatives were recruited, and the political and ideological stakes were thus heightened, if not exacerbated. Could this young elite be abandoned to the influence of the Roman Church and the interests of private industry? Was it acceptable for the University, reputed by some to be Voltairean, to impose an irreligious spirit on them?

The draft submitted by Guizot in February 1836 attempted to satisfy both sides by maintaining the University, to which he was personally and professionally attached, and by establishing alongside it a freedom the exercise of which was subject to strict conditions. Discussion of the text did not begin until 14 March 1837. Lamartine summed it up well in his speech of 24 March: «Some people are concerned about the ghost of Jesuitism which is constantly being conjured up here and which would have to be declared more powerful than ever if it had the strength to make us back down in the face of freedom. The others seem to apprehend that the clergy does not exclusively possess youth, and that the spirit of the times represented by the University exercises a monopoly over the traditional and religious element represented by the teaching bodies». It was this dual discontent that led the deputy to support «the sincere and courageous minister». As in 1833, Guizot had pointed out that «everything that is of general interest, everything that relates to the major moral interests of citizens or families is a matter for the State alone», and that at the same time religion is «the most effective means of restoring to souls that inner and moral peace without which you will never re-establish external and social peace». From the competition opened up by the law and which would be imposed on private institutions, Guizot expected, he told the deputies clearly, «the triumph of public establishments, which is necessary in the interests of society». It was also an opportunity for the Minister to proclaim the primacy of classical literature over scientific and vocational education, the development of which had been called for by the Saint-Simonians as well as by scientists such as Arago, and to state firmly that the minor seminaries could only exist and receive public aid if they confined themselves to their sole mission of training priests.

The bill was therefore passed on 29 March by 161 votes to 132, indicating a hesitant majority. Two weeks later, Guizot was no longer Minister, and the draft adopted at first reading disappeared with him. Back in power on 29 October 1840, Guizot, who was devoting more and more of his time to his department of Foreign Affairs, let his colleagues in Public Education, Villemain in 1841 and 1844, and Salvandy in 1847, table and sometimes discuss projects relating to secondary education without pushing them very hard, as he realised that the political situation and the state of mind made this impossible. In fact, he confined himself to repeating his main principles, as in his speech of 31 January 1846, which was enthusiastically applauded but never followed up: «The King's government is firmly resolved to fulfil the promises of the Charter (i.e. freedom of education). It is firmly resolved to maintain the State's rights over public education. He is also firmly resolved to maintain religious peace in the presence of religious freedom and freedom of thought, the coexistence of which is the honour of our society». The fact remains that, unlike primary education, secondary education under the July monarchy did not enjoy the hoped-for benefits of this dual freedom. It is to the progress of the latter that François Guizot's name remains attached, as he himself did.

To find out more, download the long version of Laurent Theis's article: François Guizot Minister of Public Instruction.