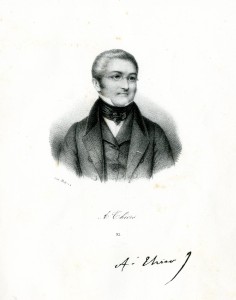

In his will dated 19 June 1839, Duke Victor de Broglie wrote of his relationship with François Guizot: «I regard our long friendship as one of the most precious possessions that God has bestowed upon me», which was the greatest expression of emotion of which this extremely modest personality was capable. This friendship, which dated back more than twenty years, was to last another thirty, until de Broglie's death on 25 January 1870. It was then that Guizot discovered this phrase, which the deceased's eldest son, Albert, passed on to him two weeks later. It was also this sentence that Guizot placed at the head of his biography of the Duc de Broglie, one of his very last works, published in 1872. To those close to him, he wrote as if in echo: «I have lost my oldest, my best and my rarest friend». Initially, nothing seemed to bring together to this degree of intimacy the great Catholic lord, descended from a line of marshals of France and brought up in Paris, and the Protestant bourgeois with no ancestors, educated in Geneva. Their temperaments were almost diametrically opposed, the former introverted, lacking in eloquence, rough and sometimes haughty at first, stubborn in his ideas and hating disorder and the unexpected, the latter infinitely sociable, a tireless orator, moving without apparent effort from one activity to another, and driven by an ambition that was almost lacking in the other. Except that they were the same age - two years older for Broglie - and that history had passed its measuring rod over them: Prince Victor de Broglie, a Liberal deputy to the Constituent Assembly and then Chief of Staff of the Army of the Rhine, was guillotined in June 1794, aged 37, two months after André Guizot. Their sons, orphans of the Terror, never denied the great principles of the Revolution, especially Broglie, who in 1795 came into contact with his father-in-law Voyer d'Argenson, a liberal who was increasingly committed to the left. Under the Empire, they barely rubbed shoulders, even though they frequented the same liberal society. In 1809, Victor de Broglie became a member of the Conseil d'État, and soon set off on missions that took him all over Europe, from Spain to Poland, and the first time to the United States.

In his will dated 19 June 1839, Duke Victor de Broglie wrote of his relationship with François Guizot: «I regard our long friendship as one of the most precious possessions that God has bestowed upon me», which was the greatest expression of emotion of which this extremely modest personality was capable. This friendship, which dated back more than twenty years, was to last another thirty, until de Broglie's death on 25 January 1870. It was then that Guizot discovered this phrase, which the deceased's eldest son, Albert, passed on to him two weeks later. It was also this sentence that Guizot placed at the head of his biography of the Duc de Broglie, one of his very last works, published in 1872. To those close to him, he wrote as if in echo: «I have lost my oldest, my best and my rarest friend». Initially, nothing seemed to bring together to this degree of intimacy the great Catholic lord, descended from a line of marshals of France and brought up in Paris, and the Protestant bourgeois with no ancestors, educated in Geneva. Their temperaments were almost diametrically opposed, the former introverted, lacking in eloquence, rough and sometimes haughty at first, stubborn in his ideas and hating disorder and the unexpected, the latter infinitely sociable, a tireless orator, moving without apparent effort from one activity to another, and driven by an ambition that was almost lacking in the other. Except that they were the same age - two years older for Broglie - and that history had passed its measuring rod over them: Prince Victor de Broglie, a Liberal deputy to the Constituent Assembly and then Chief of Staff of the Army of the Rhine, was guillotined in June 1794, aged 37, two months after André Guizot. Their sons, orphans of the Terror, never denied the great principles of the Revolution, especially Broglie, who in 1795 came into contact with his father-in-law Voyer d'Argenson, a liberal who was increasingly committed to the left. Under the Empire, they barely rubbed shoulders, even though they frequented the same liberal society. In 1809, Victor de Broglie became a member of the Conseil d'État, and soon set off on missions that took him all over Europe, from Spain to Poland, and the first time to the United States.  The Restoration led him to the Chamber of Peers. His first public exploit was, in December 1815, to publicly refute in the Chamber the charge of high treason against Marshal Ney, which did not save the latter, but earned the young peer a great reputation for independence of spirit. In February 1816, against the advice of his family, who saw it as a misalliance, he married Germaine de Staël's daughter Albertine, to his great delight. Joining this Swiss, Protestant and liberal family brought him closer to Guizot. Both were appointed conseillers d'État in ordinary service in 1817, and it was in this year that they really met, putting their legislative and legal skills for Broglie, and their political, administrative and drafting skills for Guizot, to work for the liberal ministries, from Richelieu to Decazes. In 1818, Broglie joined the group of «doctrinaires» of which Royer-Collard and Hercule de Serre were the leading figures, and Guizot the active agent. From then on, wrote Guizot, «the closer we lived to each other, the more we became, from event to event, I could say from day to day, and almost without expressing it, more serious and intimate friends». This friendship, which allowed the utmost frankness between them, was born of politics, and was to thrive on it until 1848. Here are the main stages: opposition to the ultra-conservative cabinets of 1820 to 1828; joint membership of the Société de la Mor morale chrétienne, which they chaired successively; rejection of the ordinances of Charles X; firm, unenthusiastic acceptance of the July Revolution of 1830, which brought them both into the government, Broglie as Minister of Public Instruction and Guizot as Minister of the Interior; active support for conservative policies; pillars with

The Restoration led him to the Chamber of Peers. His first public exploit was, in December 1815, to publicly refute in the Chamber the charge of high treason against Marshal Ney, which did not save the latter, but earned the young peer a great reputation for independence of spirit. In February 1816, against the advice of his family, who saw it as a misalliance, he married Germaine de Staël's daughter Albertine, to his great delight. Joining this Swiss, Protestant and liberal family brought him closer to Guizot. Both were appointed conseillers d'État in ordinary service in 1817, and it was in this year that they really met, putting their legislative and legal skills for Broglie, and their political, administrative and drafting skills for Guizot, to work for the liberal ministries, from Richelieu to Decazes. In 1818, Broglie joined the group of «doctrinaires» of which Royer-Collard and Hercule de Serre were the leading figures, and Guizot the active agent. From then on, wrote Guizot, «the closer we lived to each other, the more we became, from event to event, I could say from day to day, and almost without expressing it, more serious and intimate friends». This friendship, which allowed the utmost frankness between them, was born of politics, and was to thrive on it until 1848. Here are the main stages: opposition to the ultra-conservative cabinets of 1820 to 1828; joint membership of the Société de la Mor morale chrétienne, which they chaired successively; rejection of the ordinances of Charles X; firm, unenthusiastic acceptance of the July Revolution of 1830, which brought them both into the government, Broglie as Minister of Public Instruction and Guizot as Minister of the Interior; active support for conservative policies; pillars with  Thiers of the cabinet of 11 October 1832, from which Broglie, Minister of Foreign Affairs, withdrew in April 1834 following an unexpectedly hostile vote concerning an indemnity to be paid to the United States; President of the Council of the same government, still with Guizot, from March 1835 to February 1836. Broglie never agreed to be part of a ministry that Guizot would not be part of, certainly out of friendship, but also because he needed the influence that his friend exerted over the parliamentary assemblies. The reverse was not true, but although Broglie sometimes spared him advice and criticism in letters in which every word was weighed up, he never made a gesture or said a word hostile to Guizot, even though he no longer sat in the government during the last twelve years of the regime - «he is as attached to power,» wrote Sainte-Beuve, "as he is to popularity". Better still, when Guizot sought his help in his relations with England, of which Broglie was a great admirer like Guizot and a perfect connoisseur, he agreed in 1845 to go to London to negotiate on the thorny subject of visiting rights relating to the slave trade, and then to become ambassador there in June 1847. It was there that the February Revolution found him.

Thiers of the cabinet of 11 October 1832, from which Broglie, Minister of Foreign Affairs, withdrew in April 1834 following an unexpectedly hostile vote concerning an indemnity to be paid to the United States; President of the Council of the same government, still with Guizot, from March 1835 to February 1836. Broglie never agreed to be part of a ministry that Guizot would not be part of, certainly out of friendship, but also because he needed the influence that his friend exerted over the parliamentary assemblies. The reverse was not true, but although Broglie sometimes spared him advice and criticism in letters in which every word was weighed up, he never made a gesture or said a word hostile to Guizot, even though he no longer sat in the government during the last twelve years of the regime - «he is as attached to power,» wrote Sainte-Beuve, "as he is to popularity". Better still, when Guizot sought his help in his relations with England, of which Broglie was a great admirer like Guizot and a perfect connoisseur, he agreed in 1845 to go to London to negotiate on the thorny subject of visiting rights relating to the slave trade, and then to become ambassador there in June 1847. It was there that the February Revolution found him.

When Guizot returned from exile in July 1849, his old friend, then a member of parliament, was in the port of Le Havre to welcome him. Broglie did nothing to reintegrate him into the parliamentary game, as he was well aware of the tensions his name aroused. Moreover, after the coup d'état of 2 December 1851, Broglie withdrew from political life, for a time unbelievingly supporting the merger between the Legitimists and the Orleanists.

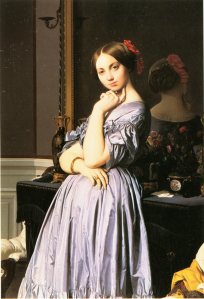

These political vicissitudes in no way diminished the friendship between Guizot and Broglie, which was tirelessly maintained right up to the last day. It was rooted in much deeper ground. Very early on, the lives of the two families became intertwined, each entering into the details of the other's existence. When Victor and his wife were able to move back to the Château de Broglie in the Eure in 1825, all the Guizots - himself, his mother, his wife and his son - were among the first to stay there. And staying at Broglie became a veritable institution for decades. Until the purchase of Val-Richer in 1836, it was at Broglie that Guizot went to bury his sorrows, show his joys, finish a piece of work and run his election campaign. Thereafter, the proximity of the two houses facilitated exchanges of visits. The eldest daughter, Louise, became Countess Othenin d'Haussonville in 1836.

These political vicissitudes in no way diminished the friendship between Guizot and Broglie, which was tirelessly maintained right up to the last day. It was rooted in much deeper ground. Very early on, the lives of the two families became intertwined, each entering into the details of the other's existence. When Victor and his wife were able to move back to the Château de Broglie in the Eure in 1825, all the Guizots - himself, his mother, his wife and his son - were among the first to stay there. And staying at Broglie became a veritable institution for decades. Until the purchase of Val-Richer in 1836, it was at Broglie that Guizot went to bury his sorrows, show his joys, finish a piece of work and run his election campaign. Thereafter, the proximity of the two houses facilitated exchanges of visits. The eldest daughter, Louise, became Countess Othenin d'Haussonville in 1836. , Albert, born in 1821, was a sort of little brother to François Guizot fils, who took him to swimming school twice a week. In 1843, Guizot launched him on a diplomatic career and, when his father died, he told him: «I ask your permission not to do anything without consulting you. You are like a second father to me». And indeed Guizot, deprived of his eldest son in 1837, had closely followed the adolescence of Albert, motherless in 1838. And Paul, the youngest son, teamed up with Guillaume for many years. And in the next generation, the links remained intact, between Broglie and d'Haussonville, Guizot and de Witt. In Broglie, in front of the tomb of Duke Victor, it was Cornélis de Witt who spoke on behalf of the Guizots. Above all, on 25 January 1870, on the last day of his life, Victor took his friend's hand for the last time, united to the end.

, Albert, born in 1821, was a sort of little brother to François Guizot fils, who took him to swimming school twice a week. In 1843, Guizot launched him on a diplomatic career and, when his father died, he told him: «I ask your permission not to do anything without consulting you. You are like a second father to me». And indeed Guizot, deprived of his eldest son in 1837, had closely followed the adolescence of Albert, motherless in 1838. And Paul, the youngest son, teamed up with Guillaume for many years. And in the next generation, the links remained intact, between Broglie and d'Haussonville, Guizot and de Witt. In Broglie, in front of the tomb of Duke Victor, it was Cornélis de Witt who spoke on behalf of the Guizots. Above all, on 25 January 1870, on the last day of his life, Victor took his friend's hand for the last time, united to the end.