«He loved me and I loved him... A true, intimate friendship, I would willingly say tender if it had to be said between men». Guizot paid this tribute to the second dearest of his friends, the first being Victor de Broglie, and shared it widely with those around him in December 1860, the day after Lord Aberdeen's death. The feeling that inspired him could indeed be called love. Nothing between them could have predicted it, and the circumstances in which it grew up and took root were hardly conducive to it.

«He loved me and I loved him... A true, intimate friendship, I would willingly say tender if it had to be said between men». Guizot paid this tribute to the second dearest of his friends, the first being Victor de Broglie, and shared it widely with those around him in December 1860, the day after Lord Aberdeen's death. The feeling that inspired him could indeed be called love. Nothing between them could have predicted it, and the circumstances in which it grew up and took root were hardly conducive to it.

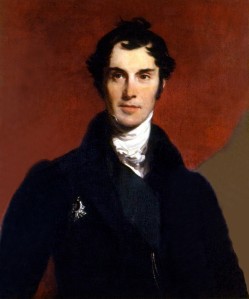

George Hamilton Gordon, born in 1784 into an old and prestigious Scottish lineage and became 4e Earl of Aberdeen in 1801, was already a household name when Guizot entered active life. He had taken part in the negotiations for the Treaty of Paris in 1814, and then held the Foreign Office for the first time from 1828 to 1830. In this capacity, he was the first foreign minister in Europe to recognise Louis-Philippe. Guizot heard more about him when he began his affair with the Princess of Lieven. Indeed, Aberdeen had more than a passing fancy for the princess, who had been a favourite of the Russian embassy in London and of the entire political and diplomatic milieu. He made this particularly clear to her one day in July 1837. But she had only recently become friends with Guizot, to whom she said: «I told him, he now knows that I am not alone on earth, that a noble heart has accepted the mission of consoling mine». The no less noble lord received the admission like a true gentleman, and without letting anything of his chagrin show, gave way before the French rival, not without declaring: «The man of whom I am most curious in Paris is M. Guizot; promise me you will make his acquaintance to me.»

The real meeting took place in March 1840, when Guizot took over the London embassy.

The real meeting took place in March 1840, when Guizot took over the London embassy.

Aberdeen, an open-minded Tory, was then in opposition: «He is very learned, and of very varied conversation.» Trust gradually grew between them, as much as the position of ambassador would allow. Aberdeen wrote to Mme de Lieven, who had remained a close friend: «The traits of his character that impress me most are his honesty and uprightness». Guizot, for his part, recognised these qualities in the man who, in September 1841, became his partner at the Foreign Office. Aberdeen had lost his father when he was seven, then his first wife and then their four children, and finally his second wife in 1833. They shared the same form of Protestantism, since Aberdeen, a Scot, was Presbyterian. Their differences lay mainly in temperament: on the one hand, the southern bourgeois, lively, prolix, perpetually on the move and in action; on the other, the great lord, an immense landowner, slow, silent, phlegmatic, whose fire burned under a thick ice that Guizot worked hard to break.

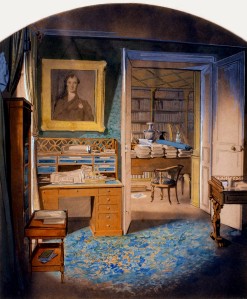

Foreign policy, which should have separated them, formed the basis of their friendship. This friendship was definitively established in September 1843, when, during the British sovereigns’ stay with the French king and queen in Eu, Guizot and Aberdeen had a tête-à-tête, in a language that is hard to imagine, as Guizot spoke imperfect English and Aberdeen almost no French, discussions that led, over the following weeks, to the establishment of a «friendship".a cordial good understanding »Louis-Philippe, inspired by Guizot, replied that there was «sincere friendship» and a spirit of «cordial understanding» between the two countries. This entente was severely tested, as the interests of the two governments often clashed: rivalry in Greece, visiting rights, Tahiti and the Pritchard affair, intervention in Morocco and, last but not least, Spanish marriages.  Despite sometimes very heated tensions, a compromise solution was found for each of these crises, until Aberdeen's withdrawal from the Foreign Office in July 1846. In addition to the meetings between the sovereigns and their ministers in Eu in September 1843, Windsor in October 1844 and Eu again in September 1845 - «In the park tête-à-tête with Lord Aberdeen. Very, very good, affectionate, trusting and sensible walk... We talked about everything», the two colleagues used an unusual procedure. From autumn 1843, in addition to official letters and dispatches, they kept up a private correspondence, the principle of which was to ’tell each other everything«, in complete frankness and confidence, including communicating to each other diplomatic documents that their respective ambassadors insisted should remain secret. Susceptibilities, misinterpretations and the pressure of public opinion were avoided in favour of mutual understanding and a desire for appeasement that did not prevent the defence of each party's interests. This »true, good and sensible« policy earned one of them the label of »bastard Englishman’ and the other «Guizot's valet» from their respective opponents, but their efforts to clear the mines bore fruit. This correspondence also bears witness to the development of their friendship, expressed above all by Guizot, whose polite expressions go from an initial «bien sincèrement» to «tout à vous» and then «tout à vous de tout mon cœur», even «du fond de l'âme» in July 1846, which is a lot from one minister to another. Aberdeen, on the other hand, was more sober, sticking to a «believe me ever most truly yours»It was an almost immovable bond. In 1847, they exchanged portraits, which hung prominently in their respective homes.

Despite sometimes very heated tensions, a compromise solution was found for each of these crises, until Aberdeen's withdrawal from the Foreign Office in July 1846. In addition to the meetings between the sovereigns and their ministers in Eu in September 1843, Windsor in October 1844 and Eu again in September 1845 - «In the park tête-à-tête with Lord Aberdeen. Very, very good, affectionate, trusting and sensible walk... We talked about everything», the two colleagues used an unusual procedure. From autumn 1843, in addition to official letters and dispatches, they kept up a private correspondence, the principle of which was to ’tell each other everything«, in complete frankness and confidence, including communicating to each other diplomatic documents that their respective ambassadors insisted should remain secret. Susceptibilities, misinterpretations and the pressure of public opinion were avoided in favour of mutual understanding and a desire for appeasement that did not prevent the defence of each party's interests. This »true, good and sensible« policy earned one of them the label of »bastard Englishman’ and the other «Guizot's valet» from their respective opponents, but their efforts to clear the mines bore fruit. This correspondence also bears witness to the development of their friendship, expressed above all by Guizot, whose polite expressions go from an initial «bien sincèrement» to «tout à vous» and then «tout à vous de tout mon cœur», even «du fond de l'âme» in July 1846, which is a lot from one minister to another. Aberdeen, on the other hand, was more sober, sticking to a «believe me ever most truly yours»It was an almost immovable bond. In 1847, they exchanged portraits, which hung prominently in their respective homes.

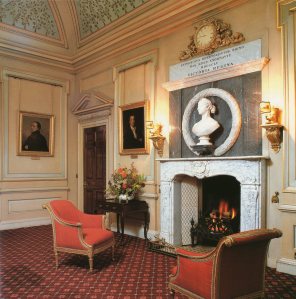

The departure of Aberdeen, the fall of Guizot, did not cool the affection, on the contrary. When Aberdeen learned that his friend had been arrested in February 1848, he is said to have felt ill. Guizot's exile in London led to some good encounters, and on his return to France he wrote: «I don't know if I have told you enough how touched I am by your friendship, and how deep mine is for you.  I certainly haven't told you as much as I should have». And he entrusted his most prized possessions to the care of Aberdeen, some of his decorations, including the Golden Fleece, and letters, including those from the Princess of Lieven. He did not recover this precious box until 1857. Outside of business, to which Aberdeen returned in December 1852 at the head of a cabinet whose existence came to a rather unhappy end in February 1855, exchanges between the two men continued in a substantial correspondence, especially as the former Foreign Office secretary became involved for a time, at the request of Guizot and others, in the process of the impossible merger between Bourbons and Orléans. Aberdeen made rare visits to Paris, and never came to Val-Richer, where the youngest of his four sons, Arthur Gordon, was warmly received. In August 1858, Guizot decided to go all the way to Scotland to see his old friend at his home, Haddo House.

I certainly haven't told you as much as I should have». And he entrusted his most prized possessions to the care of Aberdeen, some of his decorations, including the Golden Fleece, and letters, including those from the Princess of Lieven. He did not recover this precious box until 1857. Outside of business, to which Aberdeen returned in December 1852 at the head of a cabinet whose existence came to a rather unhappy end in February 1855, exchanges between the two men continued in a substantial correspondence, especially as the former Foreign Office secretary became involved for a time, at the request of Guizot and others, in the process of the impossible merger between Bourbons and Orléans. Aberdeen made rare visits to Paris, and never came to Val-Richer, where the youngest of his four sons, Arthur Gordon, was warmly received. In August 1858, Guizot decided to go all the way to Scotland to see his old friend at his home, Haddo House.

This journey sounds like a farewell. In the admirable park, the two men, already from another time, chatted, half walking, half on a bench. Guizot saw with his own eyes this aristocracy still alive, not so far removed from Walter Scott's stories: «He has more than 900 farmers. He is the last of the great laird It is impossible to let more spirit and heart shine through slow, cold forms that are sometimes a little embarrassed, sometimes a little ironic». The two friends parted in a scene as beautiful as the antique.

Aberdeen, patriarch surrounded by his family, shook Guizot's hand with these words:

«We shall not meet again; but I shall never forget that you came so far for me.»

And the other commented: «I'd go a lot further to see him again.»

He left with a watercolour of Haddo House done for him by Aberdeen's daughter-in-law, which he immediately placed at Val-Richer.

Guizot's last letter to Aberdeen was dated 11 October 1860. In July, he had written to him: «Outside your intimate family, there is no one who thinks of you more often and more affectionately than I.» Unlike his other dear friends, Guizot did not write a portrait of Aberdeen. But his correspondence is full of him: «Devious in appearance like an Englishman, tender like a woman... All the qualities of his nation without its faults. Proud and modest»; «He was really the most English character and the most European spirit I have met in his country. Being as conservative as any of his contemporaries, he was the most liberal of them all.» Is this part of a self-portrait?