That time, the early nineteenth century, was particularly conducive to the study of history. After the unprecedented events that had shaken France and Europe between 1789 and 1815, it was up to the new generation to explain what had happened - how had it come about? - and to understand the world they were entering, so that they could do something about it. For these young liberals, among whom Guizot was the eldest, access to politics had closed with the hardening of the Restoration. Augustin Thierry, Thiers, Mignet and Michelet turned their attention to history, which, far more than philosophy, now appeared to be an effective means of understanding the world, society and man himself. When, after a five-year break, Guizot resumed his lectures at the Sorbonne in 1820, he devoted them to the history of the origins of representative government, which was not unrelated to the politics of the time. When, in 1828, he regained the chair from which he had been dismissed in 1822, he chose to deal with the history of civilisation, first in Europe and then in France. Here again, the aim was to show, with intellectual rigour, how Western societies, France in the forefront, had over the centuries developed into nations and endowed themselves with institutions capable of supporting their emancipation. The concept of the history of civilisation, which Guizot is rightly considered to have invented, proved to be particularly relevant: «It is», he told his spellbound students, «the summary of all histories; it needs them all for its materials, because the fact that it recounts is the summary of all facts». Total history, in a way.

The Revolutions

Like his historian colleagues and friends, Guizot was obsessed by the French Revolution, which had affected him personally through the execution of his father. But, unlike Mignet, Thiers, and later Tocqueville and Michelet, he did not deal with it directly, choosing to take the diversions of England. As early as 1823, he undertook to study how representative government, in other words constitutional monarchy, had developed and thus how the revolution had succeeded in England between 1640 and 1688 whereas it had failed in France between 1789 and 1815. Guizot devoted six volumes to this undertaking, published between 1826 and 1856, not counting other related publications, the main one being the Discourses on the history of the English Revolution, written in 1849 and placed at the head of a republication of the first volumes in 1850, one of the most powerful texts of political history in our literature, of which the following are the first sentences: «I would like to say what causes gave in England to the constitutional monarchy, and in English America to the republic, the solid success that France and Europe are pursuing until now in vain, through these mysterious tests of the revolutions which, well or badly undergone, grow or mislead nations for centuries».»

Governance and knowledge

For Guizot, history and politics were never far apart. However, they were in separate rooms, and he never exploited one for the benefit of the other, just as the statesman did not absorb the historian: sometimes it was quite the opposite. His governmental action proves this: it is true that it was with a view to legitimising the July monarchy and linking it to national continuity that he encouraged the study of French history, but it was as a historian that he acted in this direction, providing the material and the means for the undertaking. Already between 1823 and 1826 he had directed the publication of a Collection of memoirs relating to the history of France from the foundation of the French monarchy to the 13th century which included twenty-nine volumes of translations that are still very useful today. As Minister of the Interior in 1830, Guizot obtained the creation of a post of Inspector General of Historic Monuments, entrusted to Vitet and then to Mérimée. Three years later, as Minister of Public Education, he sponsored the foundation and development of a Société de l'Histoire de France, which he chaired from 1866, succeeding his friend Barante, and whose aim was to «popularise the study and appreciation of our national history in a spirit of healthy criticism, and above all through the research and use of original documents». And indeed the Society, which still exists, has published documents as considerable as, as early as 1841, the complete trials of Joan of Arc, with all the scientific rigour possible. But in every respect, national history was too important to be left in the hands of private initiative alone. The State had a direct interest in it: «It is up to the Government alone», wrote the Minister of Public Instruction, Guizot, in a report to the King in 1833, «to be able to accomplish the great task of a general publication of all the important and as yet unpublished material on the history of our country». The deputies voted the necessary credits to launch this operation on an unprecedented scale. Then, in July 1834, the Minister set up a «Committee responsible for directing research and the publication of unpublished documents relating to the history of France», which still exists today under the name of Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. The minister chaired the committee in his official capacity, surrounded by eleven members, including Villemain, Daunou, the general custodian of the Archives of the Kingdom, where Guizot had appointed Michelet head of the history section, Mignet and Vitet, and also pure scholars such as Champollion-Figeac and Guérard. Most of them also belonged to the council of the Société de l'Histoire de France, which, along with other learned societies, was called upon to work in concert with the Ministry. A plan was drawn up to locate, collect, inventory and publish documents of interest. Augustin Thierry, a friend of Guizot's, was asked to direct the collection of charters granted to communes and medieval guilds, in order to «bring to light the many and varied origins of the French bourgeoisie, that is to say the first institutions that served to liberate and elevate the nation». Ideology was not far away, but the publications, which appeared from 1835 onwards, met the demands of scholarship. That same year, Guizot set up a second committee, «charged with helping to research and publish unpublished monuments of literature, philosophy, science and the arts considered in their relation to the general history of France». This was to make the history of civilisation a government programme. Victor Cousin, Mérimée, Victor Hugo and Sainte-Beuve were all invited to take part. Thus Guizot, also a political educator, set out to create a national memory, not through commemorations, but through the exercise of the scientific spirit.

Scientific rigour

This scientific spirit, in keeping with the means available at the time, was indeed his historical trademark, much more so than that of Augustin Thierry or Michelet, who were less rigorous and more passionate. Guizot used footnotes very early on, at a time when they were not yet de rigueur even in serious works. The critical apparatus of the’History of the English Revolution is a model of its kind. Guizot relied as much as he could on first-hand documents, which he obtained through his ever-expanding network of contacts. He kept his bibliography very up to date, taking care to use the most recent or reliable editions. Even the’History of France as told to my grandchildren shows that it knows and uses the most recent work.

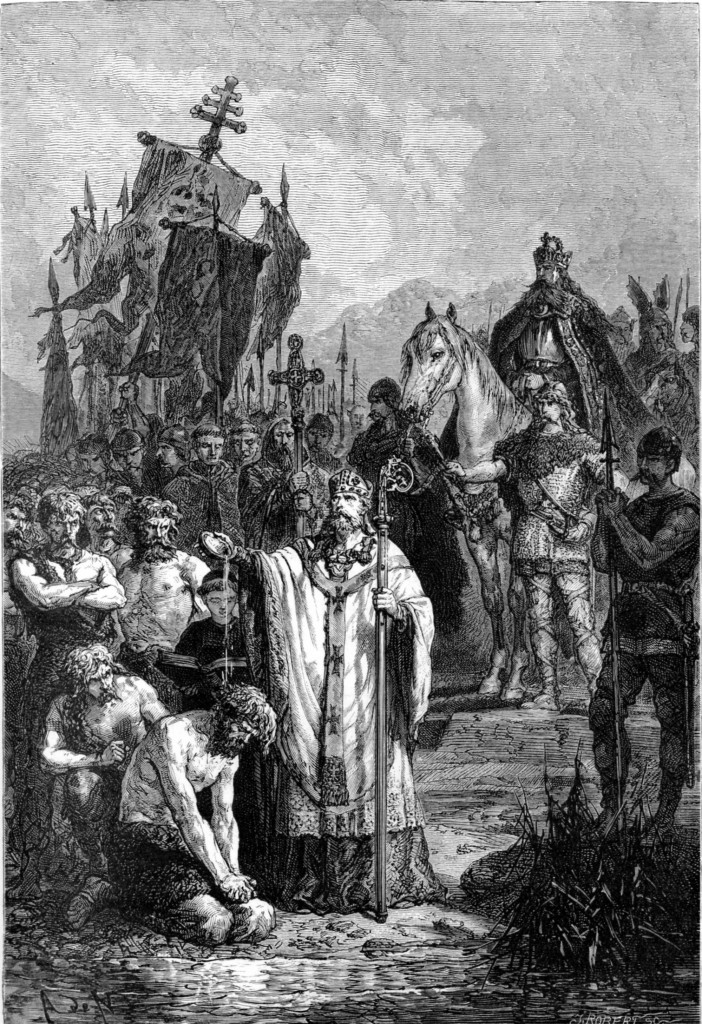

This demand for precision and information was in line with his own conception of history, which he wrote in 1828 consisted of three elements: «the facts themselves, external and material; the natural forces and laws, general and unchanging, according to which the facts are related and modified; the free acts of man himself, the moral life of individuals within the social life of the human race». The result is a determinism which, without being mechanistic, looks much more to the deep forces at work in societies than to cyclical accidents or individual characteristics as the causes of the history of men in society. Truly public history,« he wrote, »is that of men who have no history«, not primarily that of great men, of whom Guizot really only singled out four: Charlemagne, Cromwell, Washington in particular, on whom he wrote an essay, and Napoleon. Attentive to economic and social factors to the point of appearing to Marx as the historian of the class struggle, Guizot was also not far removed from what would much later become the history of mentalities when he wrote, with reference to the Merovingian period: »Are these beliefs from the cradle of the peoples, these monuments of their lively and naive credulity, less curious to study than the clear and certain events of their political careers? These fables tell us much more about the state of minds and customs than these chronicles without miracles, in which there is nothing but a few dates and a few names". The determinism - or fatalism, as it was called at the time - that animated the thinking of this convinced Christian led him to rule out any providential intervention in the evolution of human communities: history as he described and analysed it did not respond to any discernible divine plan, even if it undoubtedly existed. Events have their own explanation, and that is why history is a domain accessible to intelligence and reason.

Guizot, anxious to dismantle and demonstrate the necessary chain of cause and effect, is not a storyteller. He delivers history lessons much more than he develops a narrative intended to entertain and please. It is not that he is unsuited to the art of portraiture, nor that he neglects the description of groups, places and even feelings. He is capable of going into detail, of narrating an anecdote, of rendering a dialogue. But he never gives in to the temptation of ornament that leads to fiction. His style, sometimes rich in formulas, is always controlled and does not lapse into exaltation. Above all, he is driven by the need for clarity.

Conclusion

The influence of Guizot as a historian was immense: Michelet, Tocqueville, Marx and Taine acknowledged their debt to him, and he introduced many young people to history, whether or not they had been his students in 1828, as Montalembert wrote to him with gratitude. He brought the conception and practice of history into the modern age, and endowed France with institutions of history and memory on which it still lives. «Camille Jullian wrote in 1897 that »although this assertion may seem paradoxical in our time, which is too hostile to Guizot, it is perhaps he who, although he did not always succeed, made the greatest effort to be nothing but a historian.«