«There are two inexhaustible, infinite things in you: tenderness and courage», wrote François Guizot to his mother in 1840, when she was looking after her three grandchildren while their father, who had been widowed seven years earlier, was away in London as French ambassador. Élisabeth-Sophie Bonicel was 75 at the time. She wore on her chest the last letter written to her by her husband André Guizot on the eve of his execution on 8 April 1794, the eternal colours of widowhood on her clothes and the tears in her eyes that, she said, had overwhelmed her almost every night since.

«There are two inexhaustible, infinite things in you: tenderness and courage», wrote François Guizot to his mother in 1840, when she was looking after her three grandchildren while their father, who had been widowed seven years earlier, was away in London as French ambassador. Élisabeth-Sophie Bonicel was 75 at the time. She wore on her chest the last letter written to her by her husband André Guizot on the eve of his execution on 8 April 1794, the eternal colours of widowhood on her clothes and the tears in her eyes that, she said, had overwhelmed her almost every night since.

This woman, who has become exceptional  was not destined to suffer. She was born into a Protestant bourgeois family from Nîmes, whose roots were in Pont-de-Montvert, at the foot of Mont Lozère. The marriage of Jean-Jacques Bonicel, a wealthy and respected solicitor, to Catherine Mathieu in 1762 resulted in a string of children, of whom Elisabeth-Sophie was one of the eldest.

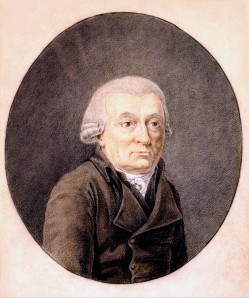

was not destined to suffer. She was born into a Protestant bourgeois family from Nîmes, whose roots were in Pont-de-Montvert, at the foot of Mont Lozère. The marriage of Jean-Jacques Bonicel, a wealthy and respected solicitor, to Catherine Mathieu in 1762 resulted in a string of children, of whom Elisabeth-Sophie was one of the eldest.  Friends and family describe her as a lively, pretty girl who loved music and reading, and was quite independent-minded. «If ever I take a husband/ I want love to give him to me», she used to sing. She found both in André Guizot, 18 months younger than herself, whom she married in Nîmes in December 1786, bringing a substantial dowry of 12,000 livres. It seems that the union was a perfectly happy one, strengthened by the birth of François ten months later: «Your father and I, well made for each other, were at that age when one feels happiness down to the marrow of one's bones». Jean-Jacques was born in October 1789. The catastrophe of 1794 shattered everything. From a cheerful and spiritual young woman, widowhood at the age of 29 and the loss of two sisters in the same years turned her into a bitter and authoritarian person, steeped in devotion, quivering with affection but incapable of expressing it. With the exception of God, her eldest son became everything to her, and she demanded that she be everything to him, constantly reminding him of his sufferings and sacrifices. A portrait of her painted by François in 1802 shows what she had become. The energy she had deployed in Geneva to ensure her children's education was restored when, widowed in 1833, Guizot entrusted her with the care of his own children and the running of his home, where she had lived for ten years. She carried out this onerous task with all the vigour and rigour of her temperament. As her granddaughter Henriette wrote, she was «steeped to the core in the traditions and doctrines of the old Huguenot spirit». Jealous, she had not looked kindly on her son's marriage to Pauline de Meulan in 1812, or even his second marriage to Eliza Dillon in 1828.

Friends and family describe her as a lively, pretty girl who loved music and reading, and was quite independent-minded. «If ever I take a husband/ I want love to give him to me», she used to sing. She found both in André Guizot, 18 months younger than herself, whom she married in Nîmes in December 1786, bringing a substantial dowry of 12,000 livres. It seems that the union was a perfectly happy one, strengthened by the birth of François ten months later: «Your father and I, well made for each other, were at that age when one feels happiness down to the marrow of one's bones». Jean-Jacques was born in October 1789. The catastrophe of 1794 shattered everything. From a cheerful and spiritual young woman, widowhood at the age of 29 and the loss of two sisters in the same years turned her into a bitter and authoritarian person, steeped in devotion, quivering with affection but incapable of expressing it. With the exception of God, her eldest son became everything to her, and she demanded that she be everything to him, constantly reminding him of his sufferings and sacrifices. A portrait of her painted by François in 1802 shows what she had become. The energy she had deployed in Geneva to ensure her children's education was restored when, widowed in 1833, Guizot entrusted her with the care of his own children and the running of his home, where she had lived for ten years. She carried out this onerous task with all the vigour and rigour of her temperament. As her granddaughter Henriette wrote, she was «steeped to the core in the traditions and doctrines of the old Huguenot spirit». Jealous, she had not looked kindly on her son's marriage to Pauline de Meulan in 1812, or even his second marriage to Eliza Dillon in 1828.  She hated the Princess de Lieven as much as she could. In summer, at Val-Richer, she sometimes found a semblance of gaiety, so fond was she of nature and particularly of flowers. In winter, at the home of her son, then a minister, she impressed visitors, as Victor Hugo did in 1846: «She attends her son's parties, seated by the fireplace, in a wimple and black bonnet, amidst the embroidery, plaques and large cords. In the middle of this velvet and gold salon, you would think you were looking at an apparition from the Cévennes. This austere yet passionate side of her appealed, for example, to Mme Récamier and Chateaubriand, whom she deeply admired and who honoured her with a personal reading of a passage from the Memoirs from beyond the grave.

She hated the Princess de Lieven as much as she could. In summer, at Val-Richer, she sometimes found a semblance of gaiety, so fond was she of nature and particularly of flowers. In winter, at the home of her son, then a minister, she impressed visitors, as Victor Hugo did in 1846: «She attends her son's parties, seated by the fireplace, in a wimple and black bonnet, amidst the embroidery, plaques and large cords. In the middle of this velvet and gold salon, you would think you were looking at an apparition from the Cévennes. This austere yet passionate side of her appealed, for example, to Mme Récamier and Chateaubriand, whom she deeply admired and who honoured her with a personal reading of a passage from the Memoirs from beyond the grave.

The revolution of February 1848 was her last test. Taking refuge with friends, she did not join her son and grandchildren in Brompton until 15 March. She was reunited with her husband, she says, on 31 March, at the age of 83. «We took her to her final resting place in Kensal Green Cemetery, Harrow-road; there is a plot there reserved for Dissenters, Presbyterian or otherwise,» wrote her son, who added: «She was one of those who must not and can scarcely be forgotten.»